Our Ancestors tell us that from the beginning of time, our people “ataaxam” have always occupied the San Luis Rey Valley, including the coastline, the neighboring lagoons, the oak forest, the lush meadows, the vernal springs, and the creeks and rivers to the north and south of the valley. The ataaxam harvested the fertile land and sea, and their extensive knowledge of the environment was passed on through culture, songs, stories and dances, from generation to generation.—The San Luis Rey Band of Mission Indians Tribal Council

It is practically impossible to read these words and fail to see how the passing of knowledge “through culture, songs, stories and dances” is directly in line with the library’s purpose, and with its mission to provide ethnic programs to diverse communities. Unfortunately, reluctance to allocating staff time and funds for cultural programming is common in budget-challenged libraries. Programs with immediately measurable results, such as computer literacy or résumé writing classes, take precedence over those whose outcome is tougher to quantify. Ethnic programs may have an additional barrier as programming librarians question how best to represent all of a community’s ethnic populations in programming—a virtually impossible task. How then does one determine a need for ethnic programs?

Had organizers of the Oceanside (Calif.) Public Library’s first Native American History celebration relied on Census Bureau statistics to determine a need for such a program, it is unlikely that the city’s reported 0.8% population of American Indian and Alaskan Native persons would have obliged them to move further than the partnership proposal by tribal members and wider community advocates like the Oceanside Arts Commission. Sometimes, as in this case, the decision to provide ethnic programs issimply a satisfying and meaningful response to a true need expressed by the community. The need from the Native American community had also been partly echoed by the community in general—that is, “Where are your Native American exhibits/programs?” Oceanside, with 167,000 residents, is a unique and diverse community. It has, for example, the largest Samoan population outside American Samoa itself, and it has large scale, multi-organizational sponsored celebrations for its more sizeable Latino and Filipino populations.

The San Luis Rey Band of Mission Indians (often referred to as “Luiseños,” given their proximity to the San Luis Rey Mission) do not have a reservation or a cultural center, which made the request from tribal members for a special program more compelling. This is an ethnicity that is deeply rooted in Oceanside’s Southern California culture and geography, yet clearly one that had been underrepresented in community programs. The San Luis Rey Band of Mission Indians, having recently organized a photographic history of its members, and with the urging of the local Arts Commission, was looking for a place to display it. San Luis Rey Band captain Mel Vernon says that the library is, in fact, the one open channel that the tribe has to share local Native American history and experience with the broader community.

“Payomkowishum,” meaning “people of the West,” was the title of a very successful and well-attended series of events that took place in honor of Native American History Month at the Oceanside Public Library five years ago. It featured lectures that highlighted librarywide exhibits of artifacts, photographs of the San Luis Rey Band of Mission Indians, and paintings by nationally renowned Luiseño and Sioux artist Robert Freeman. Artifacts were on loan from tribe members; the private collection of Paul Price, an experienced scholar of Luiseño culture; and the San Diego Museum of Man. Additionally, local basket weavers demonstrated material gathering and weaving techniques, and Native Talk, a group of Luiseño storytellers, captivated audiences with tales of ancestors as they once thrived in the local landscape. The library’s collection of relevant books and material were emphasized in the Payomkowishum display and at all related library programs.

As a programming librarian, it is extremely gratifying to work on a program such as this one. The results exceeded expectations and also created an enduring partnership between

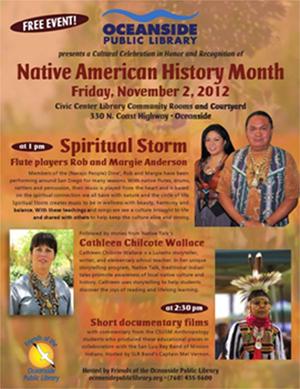

Oceanside Public Library and the San Luis Rey Band of Mission Indians. Payomkowishum has since been followed by annual events celebrating indigenous cultures that have included popular programs such as author Gordon Johnson reading from his book of short stories Rez Dogs Eat Beans and Other Tales; a photographic display and lecture titled “Edible, Medicinal, Material, Ceremonial: The Ethnobotany of Southern California Indians” produced by Rose Ramírez and Deborah Small; and a lecture about the series of paintings titled “The Spiritual Battle for Mesa Grande” by artist Raymond Lafferty. This year, the library partnered once again with the San Luis Rey Band of Mission Indians to present native flute players Spiritual Storm, storytellers, and documentary films about the Luiseño produced by local college students.

Planning and installing the original Payomkawishum exhibit was not without its challenges; organizing librarians made sure that exhibit items were reviewed before displaying. Some items on loan from the museum, such as pipes used in sacred ceremonies, were not featured in the cases and were properly protected and stored as requested by tribe members. This was meticulous and fascinating work, as scholar Paul Price detailed the use and significance of items for the exhibit and Luiseño tribal elders added their knowledge to the process. It was also essential that organizing staff understand the difficulties that indigenous people had with the concept of “borrowing” items that belonged to their ancestors, and make sure tribal members were satisfied with the library’s approach.

Not only did the Payomkawishum event lay the foundation for the library to continue to offer Native American themed programs, it convinced library administration and staff that such programs were possible using moderate staff time, funds, and local resources. Anecdotal evidence suggests that Native American programs have improved the Luiseño perception of the library. These programs have had wide appeal—at the November 2, 2012, event, parents and children, San Luis Rey Mission Band members, high school and college students, and retirees alike participated in the event. Luiseño elder Clara Foussat Guy, a regular attendee of library events since Payomkawishum, shared her childhood experiences with students who took copious notes. In the current strategic planning process, staff is looking for ways to better measure response to programs at the time of events and through changes in use of the library, such as more visits from members of particular ethnic groups.

Ethnic program planning and implementation requires all the protocol and consideration that any library programming requires, and then some. First, it is essential to clarify the expectations of the library and community partner. What is the end goal of the community partner? The answer can vary from achieving certain numbers of program attendees to the simple goal of providing community awareness to a target audience. It is also important to detail the library’s expectation to the community. It is usually helpful to community groups to have information about how a “typical” library program goes—from number of attendees, to introductions, to how the event will close. The answers to these questions will certainly assist in program development, implementation, promotion, and success.

Of course, do your homework. Learn as much as you can about the culture that will be represented in programs; if community groups or liaisons are not available; contact one of the American Library Association’s Ethnic Caucuses. The resources are easier to find and work with than you may think, and the value to the library and community is far more than worth the effort. In Oceanside Public Library’s case, ethnic programming had frequently been thought of in the context of major grant- or corporate-funded projects. While these approaches have been extremely helpful and will continue, success with individual ethnic groups shows that a path is open for future planning initiatives tied in to study of community needs, with surveys, focus groups, etc., as well as reaching out for contacts with groups found by individual staff effort. Oceanside staff and administration are highly motivated to expand and reinforce its efforts to make ethnic programs a regular experience for its community and users, and another indicator of the library’s critical role in the future.